Patients with Bartonella species infection (bartonellosis) complain of a variety of nonspecific vision problems that can affect every function of the eye. Making diagnosis and treatment decisions even more difficult, these problems can be caused by a variety of other pathogens and diseases. Fortunately, many peer-reviewed case publications, especially in ophthalmology journals, are available that describe both common and uncommon eye symptoms caused by bartonellosis.

Documented links between Bartonella species infection and vision problems focus on Bartonella henselae (cat scratch disease) and Bartonella quintana (trench fever). B. henselae is associated with contact with animals and vectors, especially cats and fleas, while B. quintana is associated with body lice. Additional species implicated include B. elizabethae and B. grahamii.

Overview

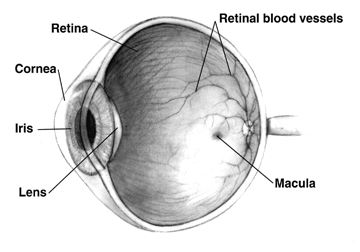

The eye consists of structures that focus light on nerve receptors at the back of the eye, nerves that feed into the optic nerve which connects to the brain, and a blood supply that connects through a central artery and vein into the body’s blood circulation. Bartonellosis can affect each of these parts of the eye.

Patients with bartonellosis-related eye problems may have symptoms in other organs as well that can help clarify whether the eye symptoms are caused by bartonellosis. Ophthalmologists and other physicians look for these additional signs because all of the eye conditions that can be caused by bartonellosis can be caused by a variety of bacteria and viruses, as well as other health conditions including autoimmune disorders.

It can be difficult to narrow down the possible causes of bartonellosis. Sometimes patients can’t remember any events that would have exposed them to Bartonella species. Other times the event, such as a cat scratch, may have occurred weeks to a month or more before symptoms appear and the patient may not think there is a connection. It can take detailed questioning by physicians to identify the possibility of Bartonella species exposure.

Structural Eye Symptoms

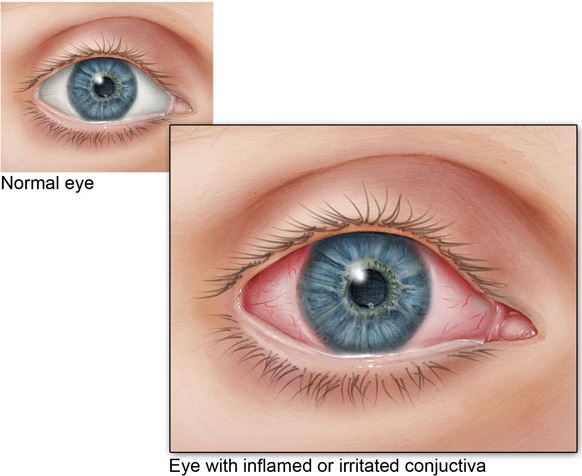

The most common way bartonellosis is seen in the eye is called Parinaud oculoglandular syndrome (POGS). About five percent of patients with acute cat scratch disease have this syndrome, which is characterized by follicular conjunctivitis (pink eye) with swollen lymph nodes nearby. It is often accompanied by a fever, and there may be bumps on the eyelid. Other symptoms known to be caused by bartonellosis, such as endocarditis (swelling of the inner lining of the heart), may also indicate that bartonellosis should be suspected.

Inflammation of the middle layer of the structure that surrounds the eyeball is called uveitis. Uveitis causes redness of the eye and can cause light sensitivity, pain and floaters. Uveitis is sometimes associated with bartonellosis.

While case reports of eye symptoms caused by bartonellosis generally describe a sudden-onset condition, one case report describes a woman who had symptoms of bartonellosis in various body organs for more than five years, including chronic conjunctivitis (pink eye). She had multiple tests and treatments over that time including a Bartonella species test that was positive but considered nonspecific. It was only after other treatments didn’t work that antibiotics were administered. The antibiotics resolved her various symptoms.

Neurological Eye Symptoms

Neuroretinitis, an inflammation of the optic nerve head, occurs in about 2% of people with cat scratch disease (acute Bartonella henselae infection). Two-thirds of cases of neuroretinitis are caused by bartonellosis.

Neuroretinitis is usually characterized by sudden, complete vision loss and swelling that creates a star pattern in the macula (the light-sensitive tissue at the back of the eye that feeds information into the optic nerve). Though this is the typical case of neuroretinitis caused by bartonellosis, it can vary greatly. It can cause changes such as seeing odd shapes or colors Furthermore, case reports have included people who lose their vision with no other symptoms, have blurry vision with a headache, and more.

Treatment can usually, but not always, restore vision, but it can take months to resolve and there can still be long-term consequences. Complications can also occur. In one case, a child was diagnosed with neuroretinitis. Treatment was started six weeks after the diagnosis, but his vision in one eye got worse. After treatment, a full-thickness macular hole was discovered. The hole was monitored and resolved after six months.

In 2019, physicians in Belgium published a case study of two patients who developed retinitis pigmentosa in only one eye. The condition was associated with bartonellosis in one of these subjects and multiple sclerosis in the other. Retinitis pigmentosa is a genetic disease that often begins early in life and leads to severe vision loss in both eyes. In these two cases, only one eye was affected and the development of the condition was associated with these other conditions. This is a preliminary report and may turn out to be a much more complex story.

Vascular Eye Symptoms

The eye has an important network of tiny blood vessels that provide nourishment to the tissue, but unnecessary growth of new capillaries can lead to a range of symptoms such as vision problems. Vasoproliferation (irregular growth of new blood vessels) may be more common in immunocompromised people, such as those being treated with chemotherapy products. These symptoms can be observed on the skin and in the liver and spleen and may also occur in the eye.

Vasoproliferative symptoms seem to be caused by vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) stimulated by bartonellosis. More research on the relationship between VEGF and bartonellosis is needed. Meanwhile, anti-VEGF agents have been used to treat vasoproliferative eye symptoms.

Conclusion

Bartonellosis can affect every part of the eye, and symptoms can be sudden and severe. Diagnosis and treatment decisions are complicated by other pathogens and diseases that can cause similar symptoms. It is important for patients and physicians to be aware of any prior animal or insect exposure that may indicate Bartonella infection. Considering additional systemic symptoms of bartonellosis may also help to clarify the diagnosis.

References

Kalogeropoulos, C. et al. (2011). Bartonella and intraocular inflammation: A series of cases and review of literature. Clinical Ophthalmology, 5, 817-829. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S20157 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3130920/

Accorinti, M. (2009). Ocular bartonellosis. International Journal of Medical Sciences, 6(3), 131-132. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2659486/

Rolain, J-M., & Raoult, D. (2012). Bartonella infections. In L. Goldman & A. I. Schafer (Eds.), Goldman’s Cecil medicine (24th ed., ch. 323, pp. 1906-1910). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders. https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/parinauds-oculoglandular-syndrome

Spinella, A. et al. (2012). Beyond cat scratch disease: A case report of Bartonella infection mimicking vasculitic disorder. Case Reports in Infectious Diseases, 2012, article 354625. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2012/354625 https://www.hindawi.com/journals/criid/2012/354625/

Woo, M. et al. (2018). A case of retinal vessel occlusion caused by Bartonella infection. Journal of Korean Medical Science, 33(47), e297. doi:10.3346/jkms.2018.33.e297 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6236082/

Fairbanks, A. M. et al. (2019). Treatment strategies for neuroretinitis: Current options and emerging therapies. Current Treatment Options in Neurology, 21(8), 36. doi:10.1007/s11940-019-0579-0 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31278547

Michel, Z. et al. (2019). Multimodal imaging of two unconventional cases of Bartonella neuroretinitis [epub ahead of print]. Retinal Cases & Brief Reports. doi:10.1097/ICB.0000000000000893 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31348120

Gunzenhauser, R. C. et al. (2019). The development and spontaneous resolution of a full-thickness macular hole in Bartonella henselae neuroretinitis in a 12-year-old boy. American Journal of Ophthalmology Case Reports, 15, 100515. doi:10.1016/j.ajoc.2019.100515 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31341998

Toumanidou, V. et al. (2017). Neuroretinitis secondary to Bartonella henselae in a patient with myelinated retinal nerve fibers: Diagnostic dilemmas and treatment. Ocular Immunology and Inflammation, 27(3), 396-398. doi:10.1080/09273948.2017.1409357 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29283743

Semes, L. P. (2018, March 23). Optic disc swelling early sign of cat-scratch neuroretinitis [sic]. OptometryTimes.com. Available at: https://www.optometrytimes.com/editors-choice-opt/optic-disc-swelling-early-sign-cat-scratch-neruoretinitis

Mabra, D. et al. (2018). Ocular manifestations of bartonellosis. Current Opinion in Ophthalmology, 29(6), 582-587. doi:10.1097/ICU.0000000000000522 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30124532

Beckerman, Z. et al. (2019). Rare presentation of endocarditis and mycotic brain aneurysm [epub ahead of print]. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2019.06.073 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31425670