Both bartonellosis and Lyme disease are associated with dangerous heart conditions that can be fatal in some cases. According to the CDC, 11 cases of fatal Lyme carditis have been reported between 1985 and 2019, however, researchers suspect there are more undetected cases. The heart has three critical aspects that can be affected by disease: electrical, structural, and muscular. It is important to know how Bartonella and Borrelia species can negatively impact all three of these.

Electrical

The electrical function of the heart causes the muscles to contract in a specific sequence for ideal blood flow. These electrical patterns can be seen on an ECG (electrocardiogram) tracing. Specific pathways carry electrical impulses at different speeds to cause the heart to beat correctly. If an impulse is too fast or too slow, the heart will beat inefficiently, which may be fatal.

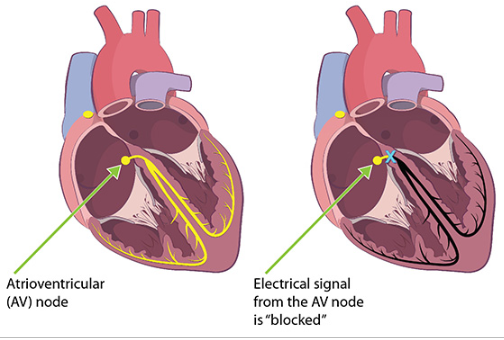

Carditis is a localized or diffuse swelling of the heart tissues. It can disrupt electrical signals in the heart, causing a “heart block.” An example of this is when the signal from the atrioventricular node (AV node) is interrupted. Less commonly, a patient may also experience atrial fibrillation, an abnormal heartbeat that can reduce the amount of blood moving through the heart.

A heart block can be detected as an abnormality on an ECG. A severe heart block can prevent the heart from getting the electrical stimulation necessary to beat, leading to sudden death.

“Lyme carditis” is carditis caused by Lyme disease. The CDC reports that this condition occurs in one out of every 100 reported Lyme disease cases, but current research suggests that the incidence is likely higher. The scientific literature suggests that Lyme carditis may occur in up to 10% of people who contract Lyme disease. It occurs when Borrelia spirochetes infiltrate heart tissue, resulting in inflammation.

Heart blocks can be treated with a pacemaker. It is important to know if the heart block is caused by Lyme carditis. If it is, the patient can use a temporary pacemaker until the carditis is resolved with antibiotic treatment eliminating the need for a permanent pacemaker.

Since these slow heartbeats are the most common result of infection, fast heartbeats can be missed as a symptom of infection. Nevertheless, different kinds of fast electrical impulses like tachycardia and premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) can also be caused by infections.

Structural

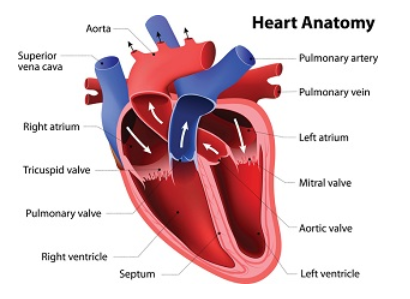

The structure of the heart valves consists of fibrous material and collagen with very little blood supply into the tissue. Healthy valves allow blood to flow through the chambers of the heart while preventing backward flow. The cells in heart valves are extremely slow-growing and slow-dividing. Consequently, valves are unable to heal the way other tissue does and are susceptible to infection.

Abnormalities in heart valves can increase the risk of infection. About one in fifty people have abnormalities in how their valves developed in gestation. As people age, their valves can develop additional abnormalities, including calcification. Genetic differences such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS) can also make valves more likely to deteriorate over time.

Endocarditis is a swelling of the inner layer of the heart. It is often caused by a pathogen that can strike these vulnerable structures. Sometimes inflammation from the pathogen causes fibrin and other materials in the blood to stick to the heart valves. As more of this material sticks together, it grows in the shape of a plant off of the heart valve. The growth is called a “vegetation” because of this shape.

If someone has endocarditis, blood samples will be taken to see if the pathogen can be identified. If no pathogen is identified, the diagnosis is “culture-negative endocarditis.” A common cause of culture-negative endocarditis in humans and animals is Bartonella species infection. A recently published case described a 28-year old patient with a history of homelessness who was positive for Bartonella quintana using PCR. Bartonella quintana is transmitted to humans via lice and is the most common species associated with culture-negative endocarditis, but B. henselae, B. kohlerae, and other species have been implicated in these cases as well.

Rarely, Borrelia species including the species that causes Lyme disease can cause endocarditis. This is most likely because Borrelia typically do not remain in the bloodstream long after infection occurs. Likewise, research shows that Bartonella can cycle in and out of the bloodstream over the course of an infection. If endocarditis causes damage to the heart valves, the patient may require heart valve surgery.

Muscular

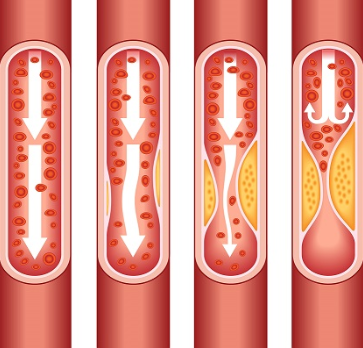

The muscles of the heart contract to move blood through the chambers of the heart. These muscles have a rich blood supply. Over time, the blood vessels supplying the heart can become damaged. Each time a blood vessel is damaged, the body makes a kind of band-aid for the damage out of cholesterol and fibrin. Eventually these build up into plaques which can block blood supply to the heart. This process is called coronary artery disease (CAD).

Find out more about the endothelium, a layer of cells inside of the heart and blood vessels.

Rarely, Lyme disease and Bartonella species infections affect the muscle of the heart directly. This can cause angina (heart pain) and damage like a heart attack. When the muscle is damaged, it releases chemicals that can be tested for in the blood. Usually heart muscle damage is caused by CAD. However, with Lyme disease, the test may be positive even though there is no problem with blood flow. In one small study, patients who were assumed to have CAD were tested for several infectious diseases; a number of them had Borrelia species infections, including Lyme disease.

Inflammation from the immune response to infectious disease can increase the cycle of damage to the heart vessels that is repaired with even more aggressive plaques, leading to earlier and more severe CAD than a person otherwise would have had. Despite this logical cause of disease, research on the association of CAD with Lyme disease or Bartonella species infections has had mixed results. It may be that the association between infectious disease and CAD involves additional variables that are unknown at this time.

Conclusion

Bartonellosis and Lyme disease can damage the heart in a variety of ways. Some of this damage may be permanent or require surgery. When a heart problem develops, it is important to consider infectious causes including bartonellosis and Lyme disease so that antibiotic treatment can be initiated and further damage or death can be prevented.

Minor updates February 27, 2024

References

Lyme carditis (2020, July 21). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases (NCEZID), Division of Vector-Borne Diseases (DVBD). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/signs_symptoms/lymecarditis.html

Hinton, R. B., & Yutzey, K. E. (2011). Heart valve structure and function in development and disease. Annual Review of Physiology, 73, 29-46. doi:10.1146/annurev-physiol-012110-142145 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4209403/

Scheffold, N. et al. (2015). Lyme carditis—Diagnosis, treatment and prognosis. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International, 112(12), 202-208. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2015.0202 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4395762/

Zainal, A. et al. (2019). Lyme carditis presenting as atrial fibrillation. BMJ Case Reports, 29(4), e228975. doi:10.1136/bcr-2018-228975 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31036741

Fatima, B. et al. (2018). Lyme disease—An unusual cause of a mitral valve endocarditis. May Clinic Proceedings: Innovations, Quality & Outcomes, 2(4), 398-401. Doi:10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2018.09.003 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6260468/

Gilson, J. et al. (2017). Lyme disease presenting with facial palsy and myocarditis mimicking myocardial infarction. Journal of Community Hospital Internal Medicine Perspectives, 7(6), 363-365. doi:10.1080/20009666.2017.1396170 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5738646/

Kubánek, M. et al. (2012). Detection of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in endomyocardial biopsy specimens in individuals with recent-onset dilated cardiomyopathy. European Journal of Heart Failure, 14(6), 588-596. doi:10.1093/eurjhf/hfs027 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22379178

Stöllberger, C. et al. (2001). Seroprevalence of antibodies to microorganisms known to cause arterial and myocardial damage in patients with or without coronary stenosis. Clinical and Diagnostic Laboratory Immunology, 8(5), 997-1002. doi:10.1128/CDLI.8.5.997-1002.2001 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC96185/

Patel, S. et al. (2019). A case of Bartonella quintana culture-negative endocarditis. American Journal of Case Reports, 20, 602-606. doi:10.12659/AJCR.915215 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31026253