According to the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), veterinary workers ranked second in incidence rates for nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses in 2016. Workers who are frequently exposed to domestic and/or wild animals are at the highest risk for acquiring zoonotic pathogens, especially Bartonella species.

Bartonellosis is a zoonotic infectious disease caused by bacteria of the Bartonella genus. Bartonella are spread to humans via scratches from infected animals as well as contact with arthropod vectors such as fleas, ticks, and lice.

The most common manifestations of bartonellosis are cat scratch disease (Bartonella henselae), trench fever (Bartonella quintana), and Carrion’s disease (Bartonella bacilliformis). You can visit our educational webpage, From Cat Scratch Disease to Bartonellosis, to learn more about each of these acute diseases. Chronic infection can lead to a variety of nonspecific symptoms that are harder to diagnose.

Although symptoms of bartonellosis have been documented by medical professionals for decades, Bartonella species were first recognized as the causative agents in the 1990s. Researchers studying HIV patients found that the presence of Bartonella in their blood led to severe symptoms including bacillary angiomatosis and endocarditis. At the time, researchers expected these atypical symptoms were limited to immunocompromised patients. Cat scratch disease and other acute Bartonella infections are traditionally considered self-limiting in immunocompetent patients. However, more recent research has found chronic infection in immunocompetent patients as well.

Case reports and research studies of high-risk groups, especially veterinarians, show that long-term Bartonella bacteremia may lead to chronic illness that is difficult to diagnose with current testing methods. This makes Bartonella difficult to fit into existing workplace injury regulations. While some regulations have been adjusted due to similar issues with Lyme disease (see our previous post on Lyme disease as an occupational risk), bartonellosis hasn’t gotten quite the same attention.

What Should Veterinarians Know?

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), in conjunction with requirements set by federal OSHA standards and recommendations provided by the CDC and National Association of State Public Health Veterinarians (NASPHV), sets guidelines for veterinary workers to protect themselves from physical, biological, and chemical hazards. Vector-borne diseases, like bartonellosis, are considered a biological hazard. Veterinary practices are responsible for developing a robust safety protocol that their workers can follow to protect themselves. No matter how thorough a protocol may be, however, accidents are bound to happen.

The normal routine for treating wounds involves filing an incident report to management and then treating the wound accordingly. Depending on the severity, a standard course of antibiotics may be warranted.

However, we now know the consequences of these encounters can continue months to years into the future. Veterinary workers exposed to vector-borne pathogens may develop chronic, non-specific symptoms long after initially being infected. The Center for One Health Research at the University of Washington recently opened the first occupational medicine clinic called the “Healthy Animal Workers Clinic” to help improve care for veterinary workers who are chronically ill.

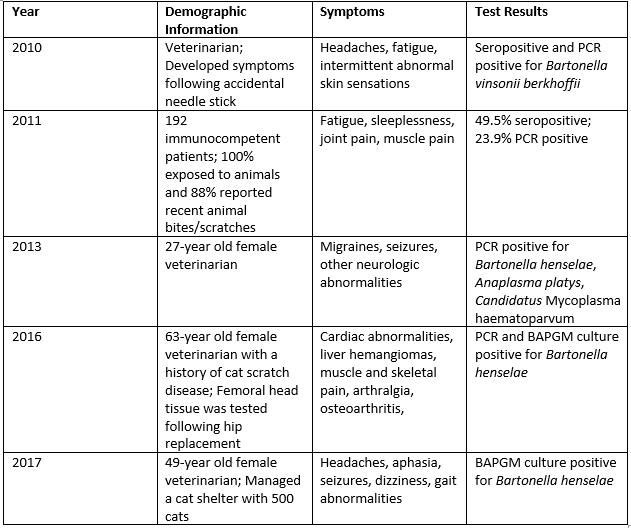

Research and case reports released over the past ten years suggest that veterinary workers and other individuals frequently exposed to animals should consider zoonotic infections such as Bartonella species when experiencing chronic illness. Documented cases include:

Conclusion

Conclusion

Veterinary professionals are at the front line of One Health, whether they are working with wildlife, agriculture, or family pets. Protecting workers from zoonotic diseases is encoded in professional and general workplace safety standards, but rapidly emerging science means that specific policies and procedures may lag. Furthermore, a future illness may not always be able to be linked to a specific safety incident. Veterinary professionals need to be aware that nonspecific symptoms may be caused by workplace exposure to pathogens.

References

Maggi, R. G. et al. (2011). Bartonella spp. bacteremia in high-risk immunocompetent patients. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease, 71(4), 430-437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2011.09.001 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0732889311003555

Maggi, R. G. et al. (2013). Co-infection with Anaplasma platys, Bartonella henselae and Candidatus Mycoplasma haematoparvum in a veterinarian. Parasites & Vectors, 6, 103 [published online]. doi:10.1186/1756-3305-6-103 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3637287/

Ericson, M. et al. (2017). Culture, PCR, DNA sequencing, and second harmonic generation (SHG) visualization of Bartonella henselae from surgically excised human femoral head. Clinical Rheumatology, 36(7), 1669-1675. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10067-016-3524-2

Oliveira, A. M. (2010). Suspected needle stick transmission of Bartonella vinsonii subspecies berkhoffii to a veterinarian. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 24(5), 1229-1232. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-1676.2010.0563.x https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1939-1676.2010.0563.x

Cheslock, M. A. (2019). Human Bartonellosis: An underappreciated public health problem? Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease, 4(69). doi:10.3390/tropicalmed4020069 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/332561606_Human_Bartonellosis_An_Underappreciated_Public_Health_Problem

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017). Zoonotic diseases. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/onehealth/basics/zoonotic-diseases.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. (2018). Veterinary safety and health. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/veterinary/work.html