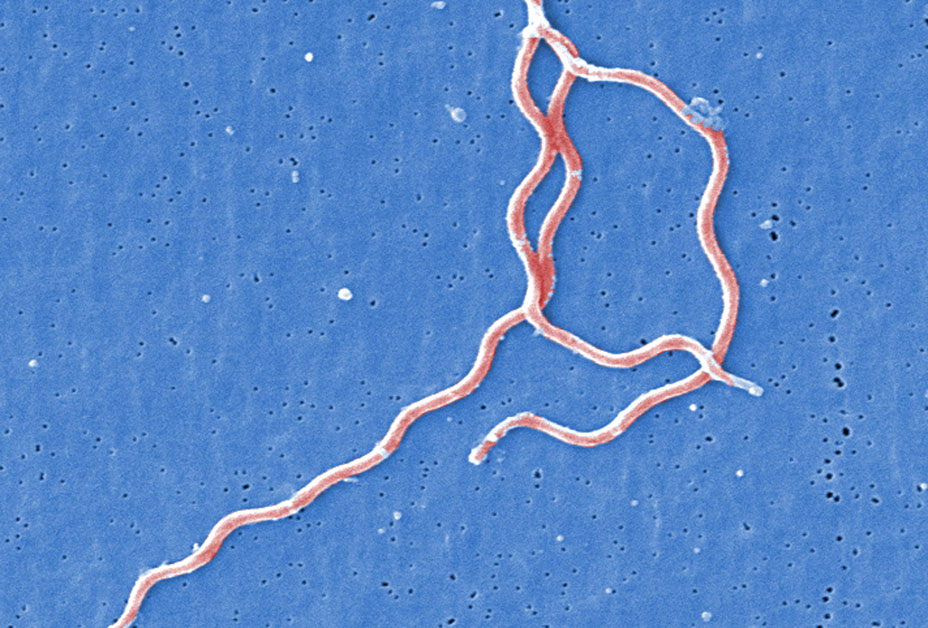

Borrelia burgdorferi s.s., the most common cause of Lyme disease, receives the most attention among the genus Borrelia. However, there are other Borrelia species that can make you sick following a bite from a tick or another vector. These include other location-specific species that cause Lyme disease, relapsing fever species which include some new interlopers that may or may not properly belong to the group, and recently discovered species that are associated with reptiles.

Causes of Lyme Disease

B. burgdorferi is the most common cause of Lyme disease in North America, however in the US it is also caused by B. mayonii. In Europe and Asia, B. afzelii and B. garinii are the primary causative agents of Lyme disease.

Genetic research suggests B. burgdorferi came from European species thousands of years ago, though it came into modern-day awareness in North America. Lyme disease was described by early North American settlers as something indigenous people and themselves experienced. As white tail deer were driven from the continent it appears that the bacteria was suppressed, coming back in the mid-twentieth century in both North America and Europe as natural landscapes were replenished. The species can also be found in Africa and Asia.

All of these species generate similar symptoms, however B. mayonii is noted for causing gastrointestinal symptoms. Serology tests for B. burgdorferi can also be positive for B. mayonii, which generates very high bacteria load so it may be easier to find on a blood smear.

Causes of Relapsing Fever

Relapsing fever is a symptom of a number of conditions and infections, including Bartonella species infections, malaria and dengue. However, “relapsing fever” is rarely part of the name of the diseases they cause. The diseases called “relapsing fever” are so named because changes in the surface proteins of the causative Borrelia species bacteria occur in a cyclical pattern that causes a matching pattern of host immune responses, including fever.

These continual shifts in immunoreactive surface proteins, or antigens, cause antibody responses that can make serology test results difficult to interpret. The antigen that is most common in relapsing fevers, glycerophosphoryl diester phosphodiesterase (GlpQ), is not typically found in species that cause Lyme disease. However, people can falsely test positive for Lyme disease even if their relapsing fever has a different cause due to cross-reactivity between antigens.

Tick-borne relapsing fever (TBRF) is caused by a variety of Borrelia species that colonize soft ticks worldwide. More species are continually being discovered. Some may only infect a few people through extremely bad luck, while others are more commonly seen.

TBRF traveled with immigrants to eastern North America going back to at least the nineteenth century, but it is not suited to becoming endemic in that region. It was introduced probably through multiple traveler sources into western North America in the early twentieth century and has become endemic. In the United States, humans are most commonly exposed in caves in Texas, but outbreaks and hot spots of generally 5-20 cases have periodically occurred across the west, with one notable outbreak of 62 cases at the Grand Canyon in 1973. In Canada, TBRF is endemic to British Columbia.

Louse-borne relapsing fever (LBRF) is caused by Borrelia recurrentis. LBRF is occasionally seen in the United States in returned travelers, with the last regional outbreak in the nineteenth century. It is spread by body lice and perhaps rarely by head lice in an area where there is high exposure to infection. LBRF was a cause of plagues in Europe going back to the 6th century, but in recent times is more commonly seen in Africa and only seen in Europe in African immigrants and returned travelers. The disease caused by the infection generally presents suddenly and severely, with fatality rates as high as 40% if left untreated.

Hard tick relapsing fever is caused by Borrelia miyamotoi. Though it generates GlpQ surface proteins, it generally creates a mild illness compared to other relapsing fevers, and some researchers do not believe it should properly be called a relapsing fever. It has some less-common cousins that may end up as their own sub-clade (taxonomic grouping) in the relapsing fever group.

Researchers were aware of it in ticks as far back as 1995 but it was not recognized as causing illness in people until almost 2011. It is likely that most people who are infected never feel sick, and those that do may be grouped in with sufferers of other tick-borne diseases and not properly identified since it is so uncommon in the clinical setting. A study using PCR to identify infections in 11,515 patients with fever and symptoms that led them to seek medical attention found B. miyamotoi DNA in 0.8% of them.

Reptile-Hosted Borrelia

A third group of Borrelia species that may infect humans are carried by reptiles. Very little is known about these species, though they have been found around the world. Sometimes more common species of Borrelia are also found in reptiles, and their role as hosts of those species is also little understood.

Conclusion

Although the symptoms caused by Borrelia species infections have been described for over 1,000 years, the bacteria responsible for Lyme disease and tick-borne relapsing fevers were only identified in the early 20th century, with research accelerating in the 1990s. Discoveries of new species and their immune-evasive techniques, like antigen shifts, make interpretation of currently available serology test results difficult. A better understanding of the prevalence of Borrelia species and your exposure risk to each of them may lead to the most appropriate testing and an earlier diagnosis.

References

Wellcome Trust. (2008, June 30). Lyme disease bacterium came from Europe before Ice Age. ScienceDaily.com. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2008/06/080629142805.htm

Bergström, S., & Normark, J. (2018). Microbiological features distinguishing Lyme disease and relapsing fever spirochetes. Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift, 130(15), 484-490. 10.1007/S00508-018-1368-2 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6096528/

Dworkin, M. S. et al. (2008). Tick-borne relapsing fever. Infectious Disease Clinics of North America, 22(3), 449-468. 10.1016/j.idc.2008.03.006 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3725823/

Warrell, D. A. (2019). Louse-borne relapsing fever (Borrelia recurrentis infection). Epidemiology & Infection, 149, e106. 10.1017/S0950268819000116 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6518520/

Telford, S. R. et al. (2015). Borrelia miyamotoi disease (BMD): Neither Lyme disease nor relapsing fever. Clinics in Laboratory Medicine, 35(4), 867-882. 10.1016/j.cll.2015.08.002 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4662080/

Panetta, J. L. et al. (2017). Reptile-associated Borrelia species in the goanna tick (Bothriocroton undatum) from Sydney, Australia. Parasites & Vectors, 10, 616. 10.1186/s13071-017-2579-5 https://parasitesandvectors.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13071-017-2579-5