When I was attending veterinary school in the 1970s, Bartonella was not known to infect animals or humans in North America.

Thus, as a young veterinarian, I had never heard of bartonellosis. It would be another 20 years before these bacteria were found in humans with AIDS in cities throughout the United States.

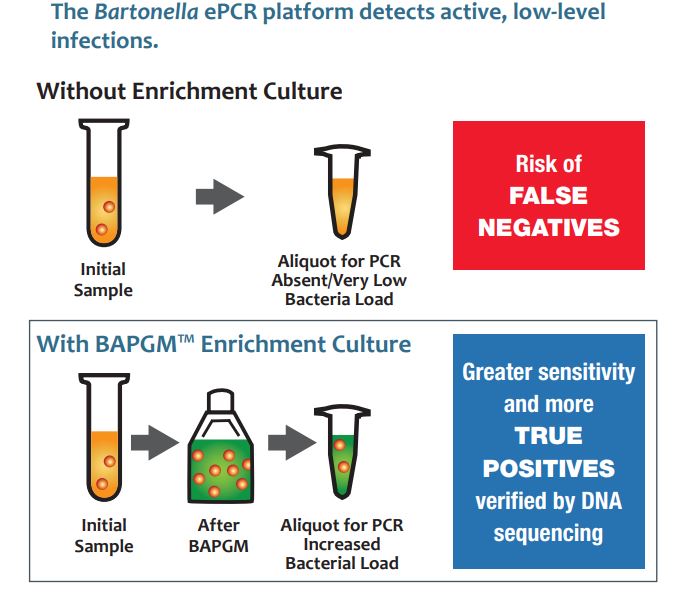

Some twenty years later, in 2009, Galaxy Diagnostics released our first commercial test. This novel diagnostic test was intended for use by veterinarians to diagnose Bartonella infection in animals (cats, cows, dogs, horses and wild animals).

At the time the test was launched, we believed the improved test sensitivity would also become important for diagnosing bartonellosis in humans. Our research was just beginning to document bloodstream infection with Bartonella species in veterinarians, veterinary nurses and others with extensive arthropod contact and animal exposures. Subsequent research confirmed that veterinary workers are at occupational risk for acquiring bartonellosis (Bartonella infection) because of their daily contact with fleas, ticks and animals. One study from our research group, published in 2014, found that 28% of veterinary workers had Bartonella DNA in their blood, indicating current infection with these vector-borne bacteria.

During the past decade, we and others have generated data that supports a medically important role for Bartonella species as a cause of cardiovascular, neurological, and rheumatic disease in humans. This information has increased the urgency of developing prevention and treatment strategies for people at an increased risk of infection.

During my veterinary medical education, James Herriot published his first book All Creatures Great and Small. Like many people who work in veterinary medicine, I was inspired by Dr. Herriot’s work and the fascinating stories he told in his books. Dr. Herriot was familiar with many infectious diseases that are shared by humans and animals on farms and in the many environments where vectors, animals and humans interact.

One disease Herriot dealt with routinely was brucellosis, caused by Brucella species. Like Bartonella species, Brucella species cause disease in animals and humans. These bacteria, which are evolutionary cousins to Bartonella, still infect animals and people throughout the world. Brucellosis diagnosed on a farm requires both an animal health and a public health response.

Historically, as scientists and clinicians, we did not routinely use the term “One Health,” but today we are very aware that it is necessary to think of the environment, people and animals as interconnected. “One Health” is critically important to how we study, treat and prevent pathogenic infections that occur in animals and people. Like the response to Brucella species, the response to Bartonella species affects both humans and animals.

We have often discovered a pathogenic Bartonella species when it is found in an accidental host, that is, in an animal where it doesn’t usually live. Then we learn more about the natural reservoir host(s). For example, our understanding of Bartonella henselae advanced rapidly after the bacteria were first isolated from a blood sample from an HIV/AIDS patient. Within a few years, researchers made the association between this “new” bacteria and cat scratch fever. Subsequently, our understanding of the medical importance of this bacteria expanded, in conjunction with efforts to define transmission among cats, an important reservoir host. This medical discovery has also propelled efforts to prevent transmission from cats (and other animals) to humans. DNA of the “new” bacteria was subsequently found in the dental pulp of cats buried with Egyptian royalty, suggesting that it is not a “new” bacteria after all. Just newly discovered.

Similarly, Bartonella vinsonii subspecies berkhoffii was first isolated from the blood of a sick dog in my research laboratory at the North Carolina State School of Veterinary Medicine, where I am a professor. Subsequently, these bacteria were found in healthy wild animals, in sick pets and in sick and healthy people around the world. Studying how vectors, bacteria (and other pathogens), pets, farm animals and people share the same environment and ultimately develop the same infections has contributed to ongoing improvements in preventive strategies.

At Galaxy Diagnostics, we work continuously to develop serological and molecular tests that provide physicians and veterinarians with the best tools available to make an accurate diagnosis of bartonellosis, borreliosis, and other vector-borne diseases of One Health importance. Researchers also use our tests to better define the biomedical importance of these organisms for the health of animals and people.

The services provided by Galaxy Diagnostics on a daily basis improve the health of “all creatures great and small” as described by Dr. James Herriot in his books so many years ago. Our goal is to help animals and people, which together will form the basis for a healthier community.

Dr. Breitschwerdt is co-founder and chief scientific officer of Galaxy Diagnostics.

References

Breitschwerdt, E. B. (2017). Bartonellosis, One Health and all creatures great and small. Veterinary Dermatology, 28(1), 96-e21. doi:10.1111/vde.12413 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28133871

Lantos, P. M. et al. (2014). Detection of Bartonella species in the blood of veterinarians and veterinary technicians: A newly recognized occupational hazard? Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases, 14, 563-570. doi:10.1089/vbz.2013.1512 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4117269/