Research shows that the tick species I. scapularis can remain active at temperatures as low as 30.9 degrees Fahrenheit. In moderate winters, the fact is that flea and tick prevention is a year-round need in most of the world. In general, however, exposure is extremely limited when temperatures are consistently below 40 degrees Fahrenheit.

Exposure to fleas and ticks does tend to be less likely during the winter, but this does not mean they suddenly disappear until spring. Unless it is extremely cold with no shelter, they may be in a dormant state awaiting warmer and wetter weather. Meanwhile, they survive in microenvironments like the soil, leaf litter, or housing structures. When there is a spike in temperature in the winter they can emerge, looking for a meal just as they do in any other season. This has been especially true over the past couple of months for the northeastern region of the United States, where the temperature has fluctuated greatly.

The warmer-than-normal winter weather this year has led to an increased observation of ticks, especially across the US northeast. Local news stations and advocacy groups based in New York have posted warnings of increased tick activity, with experts describing how this may affect tick populations not only now, but also during the upcoming spring. The Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies, which is working on the TICK Project with partners that include the CDC and NY State Department of Health, warned that the abnormally warm and rainy winter is extremely amenable to the survival of ticks. Without a prolonged cold snap, juveniles and eggs are more likely to survive until the spring. This same trend is likely true for fleas.

So how do they survive in the winter?

Ticks

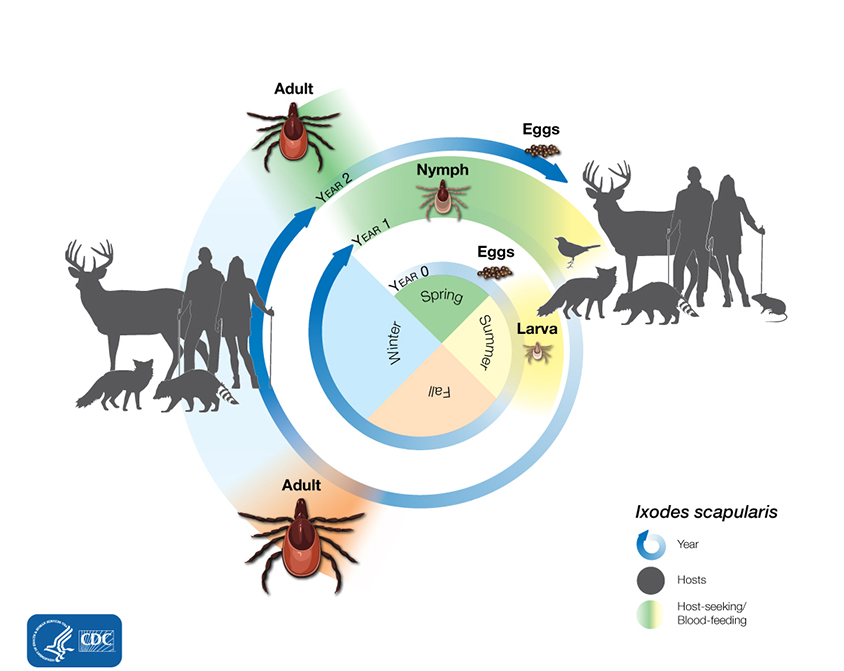

The lifecycles of Ixodes scapularis and Ixodes pacificus, the primary vectors for Lyme disease in the United States, is generally about 2-3 years and involves distinct developmental stages that each require a blood meal from a new host. This means that survival through seasonal changes is necessary for females to reach adulthood and successfully reproduce.

After hatching from their eggs, larvae have the main goals of feeding through the summer and fall and surviving the winter. Typically, they do this by remaining in a dormant state within the insulation provided by leaf litter and snow. Unless the ground is frozen for some time, they can survive until the spring, when they will feed on a new host as nymphs. If the weather warms up, however, they can emerge from dormancy at any time to feed. Studies show that Ixodes scapularis can be found questing in New York from January to March when the weather permits. Dermacentor variabilis can become active as early as February.

Interestingly, one species responsible for transmitting tick-borne diseases can complete its entire lifecycle on one indoor host, avoiding the outdoor weather entirely. Commonly called the brown dog tick, Rhicephalus sanguineus is known for residing in kennels and around heated homes year-round. They successfully reproduce just by feeding on dogs, unlike most other species of ticks that require various hosts. Furthermore, they release from the hosts at night rather than during the day, so they easily make it into people’s homes.

Fleas

Unlike most ticks, the survival of eggs or juvenile fleas through cold weather is not necessary to successfully reproduce. This is because fleas generally have a short lifespan of a few weeks to a couple of months. When temperatures are optimal (around 75 degrees Fahrenheit and 70% humidity), cat fleas (Ctenophalides felis, found on cats, dogs and a variety of other hosts in most parts of the world) can complete their entire lifecycle, from egg to adult, on a single host in just a couple of weeks.

Research suggests that adult fleas do not withstand temperature fluctuations in their environment well, but pre-emerged adults residing in cocoons can. They will remain in a protective casing for weeks to months depending on the species. Emergence in an unfavorable environment will not occur until the presence of a potential host is obvious. The flea within the cocoon may be alerted to the presence of a host by vibrations, rising levels of carbon dioxide, and body heat.

Conclusion

Vigilance against fleas and ticks is required year-round. Talk to your veterinarian about flea and tick prevention for your pets and follow best practices to protect yourself from flea and tick exposure, even in winter.

References

Elfenbein, H. (2019). Do fleas die in the winter? PetMD.com. Available at https://www.petmd.com/dog/parasites/do-fleas-survive-winter

Santa Maria, C. (2019). Ticks can survive cold weather, so keep checking your pets. TheWeatherNetwork.com. Available at https://www.theweathernetwork.com/news/articles/ticks-can-survive-winter-and-cold-weather-lyme-disease-deer-tick-pets-cats-dogs-new-boston-new-hampshire/122254/

Silverman, J. et al. (1981). Influence of temperature and humidity on survival and development of the cat flea, Ctenocephalides felis (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae). Journal of Medical Entomology, 18, 78-83. doi:10.1093/jmedent/18.1.78. https://academic.oup.com/jme/article-abstract/18/1/78/2219813?redirectedFrom=fulltext

Gage, K. L. et al. (2008). Climate and vectorborne diseases. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 35, 436-450. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2008.08.030 static1.1.sqspcdn.com/static/f/551504/6467299/1270769608913/Gage+et+al.pdf?token=6mCSf%2Fqe2MuEW94lHok5ONl9%2Fhk%3D

Ostfeld, R. (2020, January/February). Ticks in winter. Adirondac Magazine. Available at https://www.adk.org/ticks-in-winter-ostfeld/

WRGB. (2020, February 3). Tick sightings spike during warm January. Available at https://www.weny.com/story/41644769/tick-sightings-spike-during-warm-january#.XjhFtTPZbQM.twitter

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). Tick surveillance. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/ticks/surveillance/index.html

Bayer. (n.d.). Companion vector-borne diseases. Available at http://www.cvbd.org/en/flea-borne-diseases/about-fleas/general-aspects/epidemiology/

Ogden, N.H. et al. (2005). A dynamic population model to investigate effects of climate on geographic range and seasonality of the tick Ixodes scapularis. International Journal of Parasitology, 35(4), 375-389. doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2004.12.013 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0020751905000044

Gray, J et al. (2013). Systemics and ecology of the Brown Dog Tick, Rhipicephalus sanguineus. Ticks Tick Born Dis. 4(3), 171-180. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2012.12.003. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23415851

Rust, Mk et al. (1997). The biology, ecology, and management of the cat flea. Annu Rev Entomol. 42, 451-73. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9017899