When mounted police officer Margie Raimondi developed fatigue and muscle pain after a year on the job, she sought medical help and tested positive for Lyme disease. After treatment she returned to work, but eventually after a fall she could no longer work and applied for workers compensation benefits.

People who have an adverse experience at work are often advised to keep detailed notes of exactly when these experiences occurred. Raimondi recalled many tick bites while she was working, but she hadn’t recorded any of them.

Despite this lack of records, she was eventually awarded workers compensation. Raimondi worked in New Jersey. If she had worked for the state of Maryland in certain jobs, the law gives the presumption to the worker that they acquired Lyme disease at work.

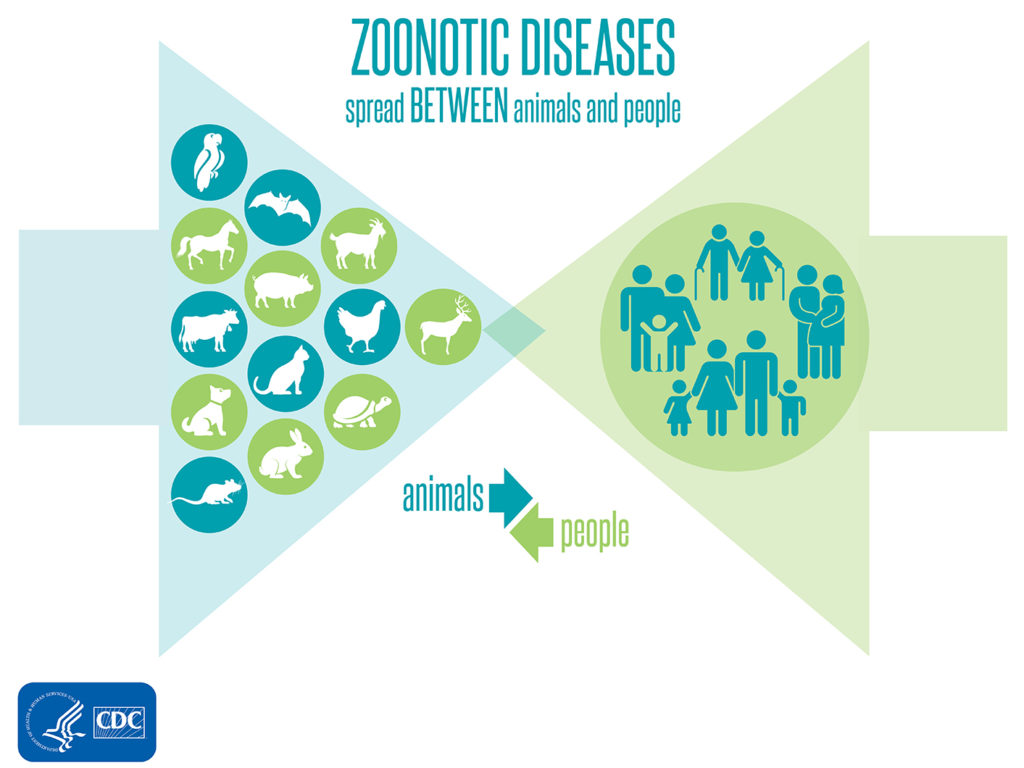

This is just one way that the law recognizes the occupational risk posed by exposure to “zoonotic” diseases. Zoonotic diseases are diseases that can be shared between humans and animals. The pathogens that cause them are transmitted in a variety of ways. For example, they can be acquired via direct contact with the saliva of an infected animal or by being bitten by infected vectors such as ticks and fleas.

Researchers estimate that approximately 60% of known infectious diseases are spread from animals to humans, and 75% of emerging infectious diseases are related to animal-human transmission. Bartonellosis, Lyme disease, and other tick-borne diseases are all considered zoonotic diseases.

“Occupational risks” are health and wellbeing risks associated with one’s job. These risks are generally categorized as chemical, biological, psychosocial or physical. Lyme disease and other zoonotic diseases are a biological risk for people who work outdoors or with animals. The level of risk an employee faces depends on the employee’s position and the geographic location of the job.

Occupational exposure to zoonotic pathogens has been researched around the world. Here are just some of the findings:

- Gardeners and Soldiers: In a study of people in the Slovak Republic, these workers were almost as likely to be positive for Lyme disease as patients with neurological symptoms waiting to be tested at a neurology clinic.

- Veterinary Workers: In the United States, Galaxy Diagnostics scientists worked with researchers at Duke University in 2014 to demonstrate that Bartonella species infection is an occupational risk for veterinary health workers. In this study, 28% of these workers were PCR-positive for Bartonella species infections.

- National Park Service Employees: A study at two major US parks found that more than a third of the employees were positive for exposure to at least one tick-borne pathogen. The risk was slightly higher for front line workers than for managers.

- Agricultural Workers and Foresters: A study in Poland found that the incidence of occupation-related diseases was 418 per 100,000 workers. Of these diseases, 92.4% were related to infectious pathogens; Lyme disease was the most common among them.

The best way for workers in these high-risk groups to protect themselves is to follow preventative measures that are recommended by their place of work and seek additional resources from organizations such as the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), a research agency directed by the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC).

NIOSH recommends that employers provide workers exposed to ticks with training on how to protect themselves from tick bites and also provide them with tick repellents and insecticides. When uniforms are used, NIOSH recommends they provide full coverage of the skin.

Where possible, NIOSH also recommends reducing the risk at work sites. This can be done by controlling rodents, small animals and deer that access the work site and by clearing leaf litter and vegetation from the work site that may support a population of ticks and tick-borne pathogens.

For those who work directly with animals, such as veterinary workers, reducing risk through safe handling of animals and universal precautions is recommended. The National Association of State Public Health Veterinarians provides standard precautions that offer guidance for reducing biological risks in a veterinary setting. Furthermore, a study conducted in Seattle, Washington found that pet owner behavior can negatively influence the safety of veterinary workers. Veterinary workers who understand the importance of safety precautions and can communicate those reasons effectively to clients can decrease their occupational risk.

Employers in the US are required by law to provide employees with the information and supplies to protect themselves from occupational risks. Employees can further protect themselves by educating themselves about how to reduce their occupational risk.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. (2011). Lyme disease. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/lyme/

Peirce III, Robert N. (2017, July 11). Business workshop: Employers can be liable for tick bites. Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved from: https://www.post-gazette.com/business/career-workplace/2017/07/11/Business-workshop-Employers-can-be-liable-for-tick-bites/stories/201707110012

Horowitz, B. (2013). Court: Morris park police officer entitled to compensation over Lyme disease. NJ.com. Retrieved from: https://www.nj.com/morris/2013/11/court_morris_park_police_officer_entitled_to_compensation_over_lyme_disease.html

Bušová, A. et al. (2018). Association of seroprevalence and risk factors in Lyme disease. Central European Journal of Public Health, 26(Suppl), S61-S66. doi:https://doi.org/10.21101/cejph.a5274 https://cejph.szu.cz/pdfs/cjp/2018/88/11.pdf

Adjemian, J. (2012). Zoonotic infections among employees from Great Smoky Mountains and Rocky Mountain National Parks, 2008-2009. Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases, 12(11), 922-931. doi:10.1089/vbz.2011.0917 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3533868/

Lantos, P. M. et al. (2014). Detection of Bartonella species in the blood of veterinarians and veterinary technicians: A newly recognized occupational hazard? Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases, 14(8), 563-570. doi:10.1089/vbz.2013.1512 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4117269/

Fowler, H. et al. (2018). Pet owners’ perceptions of veterinary safety practices. Veterinary Record. doi:10.1136/vr.104624 Retrieved from: https://veterinaryrecord.bmj.com/content/vetrec/early/2018/09/05/vr.104624.full.pdf?ijkey=p0v5nayE52lXdLT&keytype=ref