Rickettsia species are infectious bacteria that are closely related to other flea- and tick-borne pathogens like Bartonella and Ehrlichia. Rickettsiosis is an umbrella term for all infections caused by these bacteria. The infections can be further classified into two categories; the spotted fever group rickettsioses (SFGR) and the typhus group rickettsioses.

Spotted Fever Group Rickettsioses (SFGR)

SFGR are caused by Rickettsia that are transmitted by ticks and typically result in characteristic rashes on the extremities, face, and/or trunk of the body. Rickettsia invade the cells that line the blood vessels of the host. When the bacteria grow and multiply, they damage the cells. The rashes are a result of blood leakage and inflammation caused by the destruction of these cells.

These spotted fevers occur globally and are caused by a range of species specific to certain regions across the world. For example, R. africae causes African tick bite fever across Africa, whereas R. conorii causes a similar affliction called Mediterranean spotted fever across Europe.

The best-known and deadliest SFGR in the United States is Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF), which is caused by Rickettsia rickettsii. The CDC made RMSF a nationally notifiable condition in the 1920s due to its high fatality rate when left untreated. In 1943, the fatality rate was as high as 27.5% of reported cases. The use of tetracycline antibiotics (doxycycline) and improved diagnostics has dramatically decreased the death rate from RMSF.

In 2010, the CDC expanded the reporting criteria to include the rest of the SFGR, like R. parkeri and R. philipii. In 2017, the CDC reported that North Carolina, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Tennessee, and Missouri accounted for 60% of reported SFGR cases.

Typhus Group Rickettsioses

The typhus group rickettsioses are a smaller group that employs a different mode of transmission than the SFGR. Rather than being transmitted by ticks, R. typhi is transmitted by fleas and R. prowzekii is transmitted by lice.

In 1944, R. typhi infection (murine typhus) was an epidemic in the United States. The infections were mostly wiped out by 1956 because of rodent control programs, but cases are still reported in California and Texas. These infections are easily misdiagnosed because of their mild symptoms and tendency not to cause a rash.

Transmission

Rickettsia species are primarily transmitted to humans via bites from infected insect vectors. Vectors acquire these bacteria from animals. These animals are referred to as “reservoirs” because they carry the bacteria but are not affected by them. The primary reservoirs for Rickettsia rickettsii (RMSF), Rickettsia parkeri, Rickettsia philipii, Rickettsia akari, and other species are rodents such as rats and house mice. Some studies have suggested that other small mammals, such as cats and opossums, can help sustain Rickettsia populations as well.

Rickettsiosis is reported across the globe, meaning there must be a spectrum of hosts and vectors that can maintain the bacteria in the environment and transmit it to humans.

The vectors for spotted fever rickettsioses are ticks, but the primary species varies depending on the ticks found in a specific geographic region. For example, R. rickettsii (RMSF) is primarily transmitted by the American dog tick (Dermacentor variabilis) in the Eastern half of the United States, while the Rocky Mountain wood tick (Dermacentor andersoni) is the primary culprit in the Northwest. The species listed below impact other specific regions of the United States:

- Brown dog tick (Rhipicephalus sanguineus)

- Gulf Coast tick (Amblyomma maculatum)

- Pacific Coast ticks (Dermacentor occidentalis)

R. africae, which causes African tick-bite fever, is transmitted by Amblyomma ticks from Sub-Saharan Africa down to South Africa. Rickettsia conorii (Mediterranean spotted fever), the primary infectious species in Europe, is transmitted by Dermacentor ticks.

Like Bartonella species, Rickettsia from the typhus group can be transmitted by infected fleas and lice. R. typhi, the cause of murine typhus, is spread by feces from fleas that feed on infected rats and cats. R. prowazekii, or epidemic typhus, is spread by Pediculus humanus corporis (human body lice). These infections are far less prevalent than SFGR, but outbreaks are still likely to occur in large populations that experience unhygienic living situations. Isolated cases in some US states, such as Texas, have been reported in recent years.

Rickettsia species can also be transmitted through blood transfusions. In a 1978 case, a recipient became ill with RMSF about a week after a transfusion from a donor who donated blood before the onset of the condition. The donor became ill three days after the blood donation and evidence of R. rickettsii was subsequently found in tissues using immunofluorescent assay (IFA). There are no reported cases of infection from organ transplant, but the CDC says that it is physiologically possible.

Symptoms

Rickettsioses typically present with similar, mild symptoms during the first 1-2 days of infection. The early stage, non-specific symptoms can include:

- Fever

- Headache

- Fatigue

- Muscle pain

- Nausea

- Chills

More specific clinical signs can develop as well and help distinguish which Rickettsia species is present:

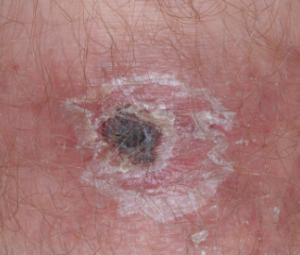

Eschars, or dark and sometimes tender scabs, are caused by the attachment of an infected tick or mite. They typically appear before or at the onset of a fever within 2-4 days of infection. These ulcerated regions are characteristic of R. parkeri, R. philipii, and R. akari infections.

Rashes of varying appearances are a common symptom of SFGR as well. R. parkeri rashes are often seen on the extremities, whereas R. akari ones can spread to the face. According to the CDC, 90% of people with RMSF (R. rickettsii) have a rash at some point during the illness. The early rash usually appears 2-4 days after infection and appears as small, flat circles on the extremities. The late rash is composed of pinpoint, red spots on the surface of the skin (petechiae) 5-6 days after becoming ill.

Infections can progress more quickly or cause more severe symptoms in children, immunocompromised patients, and people who are over the age of 60.

It is recommended that patients seek medical attention as soon as possible if rickettsiosis is suspected. The majority of Rickettsia infections are mild and patients recover without immediate treatment, but RMSF can have long-term effects on the organs or be fatal if treatment does not commence early enough.

References

Blanton, L. S., & Walker, D. H. (2017). Flea-borne rickettsioses and Rickettsiae. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 96(1), 53-56. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.16-0537 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5239709/

Blanton, L. S. et al. (2019). Rickettsiae within the fleas of feral cats in Galveston, Texas. Vector Borne and Zoonotic Diseases (published online). doi:10.1089/vbz.2018.2402 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30835649?fbclid=IwAR0Hnv09zNhPiRjr8bzJVdCQOt5WRYGNTG95m_PNb3nPg_8WOgIIX3xLXsc

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019a). Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF). Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/rmsf/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019b). Other spotted fever group rickettsioses. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/otherspottedfever/

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019c). Typhus fevers. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/typhus/

Wells, G. M. et al. (1978). Rocky Mountain spotted fever caused by blood transfusion. Journal of the American Medical Association, 239(26), 2763-2765. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/418193