In their recent report to congress, the Tick-Borne Disease Working Group (TBDWG) emphasizes the importance of tick-borne disease surveillance, specifically for Lyme Disease. In this post, we will explore what Lyme disease and co-infection surveillance looks like now and what an improved surveillance system might look like.

As mentioned in our recent Bartonella prevalence post, it is difficult for public health professionals and researchers to determine how many people suffer just from bartonellosis. When expanded to all tick-borne diseases and co-infections, the identification process becomes even more complicated. The CDC currently only recognizes 13 unique human tick-borne illnesses caused by 18 different pathogens in the United States.

The current human surveillance system does not interact with current tick surveillance efforts. As ticks expand their range, even crossing national borders, tick surveillance efforts focused on limited species become even more disconnected from human health. Tick-borne diseases are transmitted by a range of ticks, with unfamiliar species, such as Haemaphysalis longicornis (Asian longhorned tick), regularly being identified.

Federal agencies currently do not have a standardized method for systematically collecting tick-borne disease surveillance data and sharing the information in a public, accessible way. Disease surveillance is a state responsibility led by the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE) in conjunction with the CDC. This traditional method is passive and involves clinicians or laboratories reporting positive diagnoses or results for notifiable conditions.

For a Lyme disease case to be included in surveillance data, a positive result on the CDC-recommended two-tier testing is required, unless it is early in the disease and the classic EM rash is apparent. However, this surveillance method does not capture all cases and not all reported cases are reflected back in the reported data with regional specificity in order to protect patient privacy. This may lead physicians in regions with few reported cases to believe Lyme disease is not a concern.

Reports of animal cases of Lyme disease can be reported with specific locations even when the number is very small, and tick surveillance can provide even more information. However, each of these pieces of surveillance is pursued piece-meal, and there is no system in place to give a holistic picture, reflecting a true One Health understanding of the bacteria.

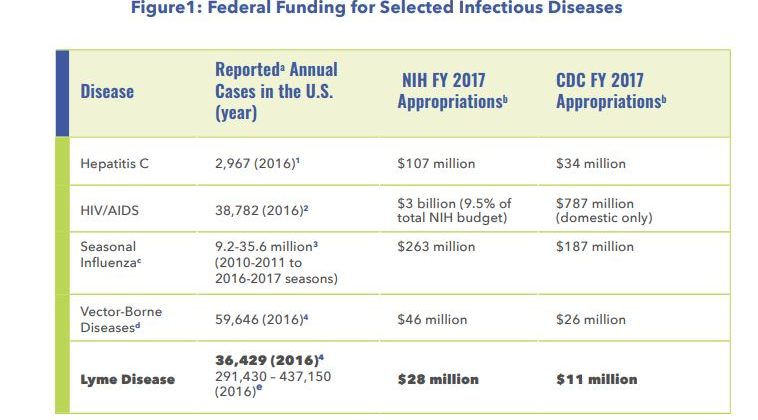

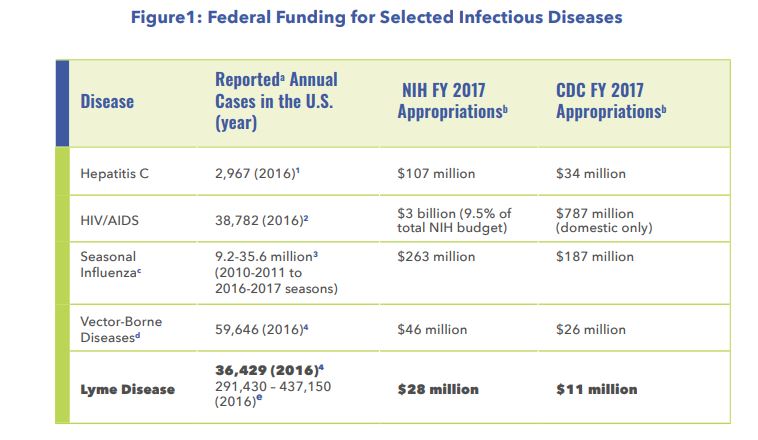

Surveillance isn’t just about knowing how many people get sick. It exists in a cycle of health activity in which the number of people who are sick affects disease funding, and funding affects the quality of surveillance. In the case of federal funding for Lyme disease in the US, funding per surveillance case is a fraction of other diseases, such as HIV/AIDS, despite having almost the same number of reported cases in 2016.

The TBDWG report includes five recommendations that suggest ways of improving surveillance of Lyme disease and other tick-borne diseases. Each recommendation is listed below along with discussion of the recommendation.

3.1 Fund studies and activities on tick biology and tick-borne disease ecology, including systematic tick surveillance efforts, particularly in regions beyond the Northeast and Upper Midwest.

The risk of exposure to ticks carrying harmful pathogens for people living in the United States is poorly understood, especially outside of the Northeast and Midwest. Researchers generally agree that geographic distributions of the most important vectors, such as the Lone-Star Tick and American Dog Tick, have expanded since these distributions were first published in 1945. However, there is not enough Federal funding to fully understand how these ticks, along with new or exotic species, distribution and behavior are changing in the face of climate and landscape changes. The TBDWG recommends systematic, standardized tick surveys at the federal level to help understand how these ecological factors drive the increasing risk of tick-borne disease for individuals at the state or local levels.

3.2 Fund systematic studies and activities to identify and characterize novel tick-borne disease agents in the United States.

Ticks can transmit a cocktail of harmful bacterial and viral pathogens when they bite their prey. Despite this fact, the scope of pathogens (bacteria, viruses, etc.) that can be found across tick species is not well understood. In 2004 alone, seven new tick-borne co-infections causing human disease were discovered, but only after they had already caused human disease. The TBDWG recommends that the microbiome of each tick species be studied using new and powerful molecular methods, such as metagenomics. Understanding what pathogens, novel or well-known, each tick species can potentially transmit will help communities evaluate their risk of tick-borne disease.

3.3 Support economic studies and activities to estimate the total cost of illness associated with tick-borne diseases in the United States, beginning first with Lyme disease and including both financial and societal impacts.

Currently, Lyme disease and other tick-borne diseases do not have comprehensive cost of illness (COI) studies associated with them. These studies analyze the economic impact a disease has on society using direct, indirect, and intangible factors, such as costs for diagnostics or doctor visits, travel costs, and the impact on emotional well-being. It is estimated that the direct cost of Lyme disease treatment alone in the United States is $1.3 billion. A COI report that fully characterizes Lyme disease could help guide policy makers on the need for more research that focuses on the improved diagnosis and treatment of tick-borne diseases.

3.4 Have public health authorities formally recognize complementary, validated systematic approaches to tick-borne disease human surveillance, such as systematic sampling of tick-borne disease reports for investigation that reduce the burden on tick-borne disease reporting but allow for comparability of surveillance findings across states and over time.

The current surveillance criteria set forth by public health officials limits novel and validated methods of studying tick-borne disease prevalence in humans. The current method is passive and relies heavily on laboratory evidence, resulting in under-reporting of Lyme disease. Therefore, the TBDWG recommends having complementary, creative, and financially sustainable methods for successful surveillance in the future. For example, a mobile app designed by TickReport provides free tick identification for people who find ticks on or around themselves. In addition, routine vector-borne disease testing conducted on companion animals provides regional data that could complement human data. The Companion Animal Parasite Council provides an interactive map that forecasts the prevalence of diseases, such as Lyme disease, for pets.

3.5 The Lyme disease surveillance criteria are not to be used alone for diagnostic purposes; public health authorities shall annually and when opportune (such as during Tick-borne Disease Awareness Month) communicate this and inform doctors, insurers, state and local health departments, the press, and the public through official communication channels, including the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR).

The TBDWG noted that not only is the surveillance case definition problematic for studying Lyme disease prevalence, but physicians and medical insurers will often use it incorrectly. The definition is supposed to be used solely for public health surveillance to establish areas of high or low incidence. However, physicians and insurance companies will often not diagnose a patient and provide reimbursement accordingly unless the criteria are met. The TBDWG recommends that the Federal government, public health authorities, and advocates in the medical community clarify this through methods of communication such as social media and websites. These clarifications should also be prioritized during opportune times, like Tick-borne Disease Awareness Month.

To find out more about what the TBDWG had to say about these recommendations, go to chapter three of their report. It is important to keep these recommendations in mind as we explore the impact the current surveillance methods have on patients’ access to care next week. For the full report, click here.

The graphics in this post can be found in the TBDWG 2018 Report to Congress.

Want to read more of our posts about the TBDWG report? Links below:

- Introduction to the TBDWG

- Human Surveillance of Tick-borne Diseases

- Access to Patient Care

- Prevention