People who have experienced symptoms related to tick-borne disease generally say they wouldn’t wish these illnesses on anyone. Despite the educational information tick-borne disease patients repeatedly provide in the media and to their friends, many people do not act to prevent tick bites when participating in activities that may put them at risk.

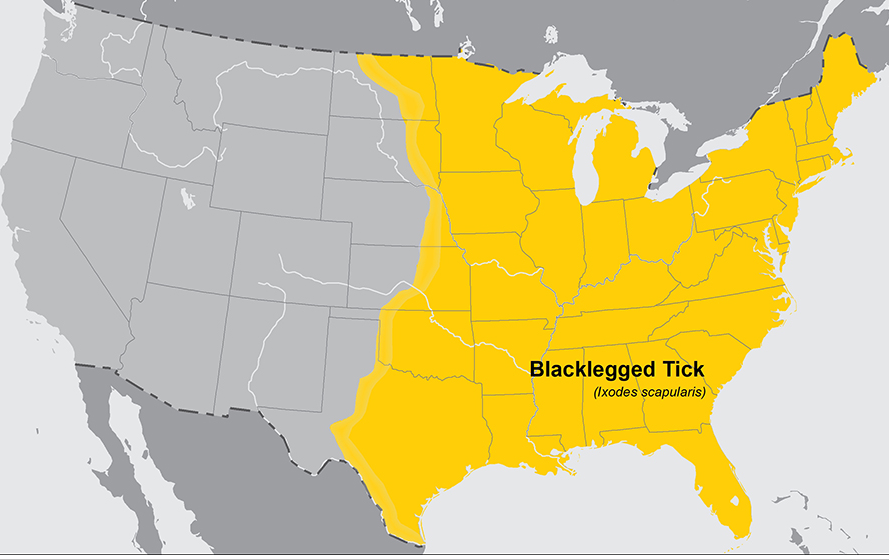

The Tick-Borne Disease Working Group report released earlier this year (we reported on it here) stated that health care providers and the public do not understand the risks of tick-borne disease. Even when they do, information about prevention may not be easily accessible. Recreational parks and trails in Lyme-endemic areas of the United States, like New York state, are more likely to have signs that warn visitors about the dangers of tick exposure. However, tick-borne disease is reported around the country and these warnings are often missing in areas where it is not as prevalent.

Currently only four products are approved as tick repellents in the US. Two of these are categorized as “natural.” Other products that have shown promise in the laboratory are not making progress to market as quickly as they could. Fortunately, there is more that can be done to prevent tick bites.

Physical

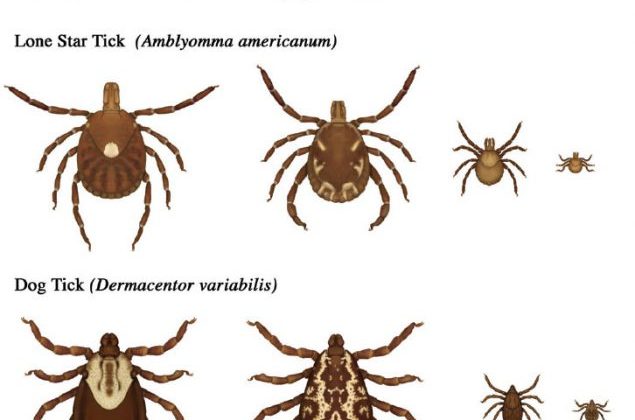

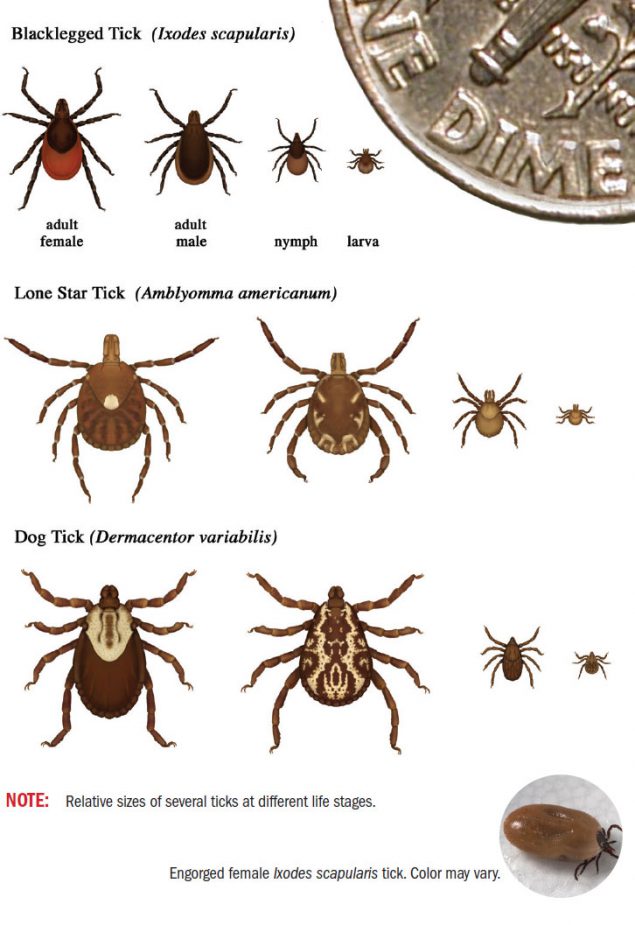

Prevention starts with wearing clothing that covers the skin. Tuck pants into socks and wear light colors so ticks can easily be seen. When spending time in an environment where ticks may be present, do a whole-body check for ticks at least once every 24 hours. Ticks vary in size depending on their life stage and species, but deer tick nymphs can be as small as a fleck of black pepper. Therefore, it is essential to pay close attention to spots that may appear as new freckles or moles.

Bryon Backenson, New York’s deputy director of communicable disease control, relies on these steps for himself and his team. More than 300 times per year they enter tick-infested environments to collect ticks for surveillance. They cannot wear repellents since they’re actually trying to collect ticks. So far, no one on his team has contracted a tick-borne disease.

Repellents

The two chemical tick repellents that are approved for human use in the US are Permethrin and DEET.

Permethrin has been developed to be similar to an extract from the chrysanthemum flower. Because of the variety of vector-borne diseases that it can help prevent, it is on the World Health Organization’s List of Essential Medicines.

While it is neurotoxic to arachnids, insects and cats, humans and dogs break it down quickly. Furthermore, less than 1% is absorbed through the skin in humans. Women who have had whole-body exposure to permethrin for scabies treatment during pregnancy have had good outcomes. However, permethrin can cause tumors in rats when eaten. It can also cause skin irritation, which is why it is generally used on clothing. It can sicken cats who get a secondary exposure from dogs or humans that have used the product.

When using topical preventatives containing permethrin on dogs, it is important to follow the usage directions on the label. Most preventatives require dogs to not be bathed within 24-48 hours of application because the natural oils the skin produces must be present for maximum efficacy. Preventing ticks on dogs helps keeps them out of homes and away from people.

An advantage of permethrin is that it can remain effective for more than 21 days after application to clothing. In addition, it does not seem to be toxic to young children. (Always check with your health care provider.)

DEET (tiethyltoluamide) is often used when the skin needs protection. A common commercial product contains 25% DEET and is effective for about four hours. DEET should not be used on infants under two months old, and DEET concentration and frequency of use should be limited on children under 12 years old. Too frequent and too heavy applications of DEET can cause poisoning even in adults, though most adults use DEET without problems. The US EPA has documented four deaths related to DEET. DEET can cause damage to some clothing.

So why do people still use DEET? Exposure to ticks in high-risk areas may make DEET risks lower than the risk of disease. For example, 5% of Appalachian Trail through-hikers contract Lyme disease.

There are also two “natural” tick repellents registered with the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and one in the review process. These repellents should not be used on children under three years old. An overview of these repellents:

- 2-undecanone is derived from wild tomato. In laboratory testing, this chemical was more effective than DEET at repelling Ixodid species ticks, including those that carry Lyme disease. However, it can cause a skin reaction, especially after repeated applications.

- Mixed Essential Oils (rosemary, lemongrass, cedar, peppermint, thyme, geraniol) are available in a variety of formulations. In testing, some formulations have proven more effective than others and effective for different lengths of time. Essential oils have been associated with allergic reactions, respiratory issues, chemical burns and other adverse reactions and may not be safe around babies or during pregnancy.

- Nootkatone is an essential oil that can be derived from several sources. In laboratory testing, an advantage of this product was that repelled ticks even at low concentrations, possibly reducing the risk of side effects.

Other products show promise as tick repellents, but none have been approved as marketed products in the US. For example, tea tree oil has been found to be effective in repelling ticks from cattle in a peer-reviewed published study, but it has not been studied and approved for human use in the US.

Conclusion

The biggest message in prevention is that tick bites are not inevitable. Tick-bite prevention works if done properly. The biggest barrier to prevention is awareness of the risk of tick-borne disease. If people do not understand the risk of tick-borne diseases, proper clothing seems like too much trouble, and thinking about the safety of tick repellents seems pointless.

This summer, let your friends and relatives know that even if they do not want to use tick repellents, they can use protective clothing. Repellents, in balance with the risk of tick-borne disease, should also be considered. With public education it is possible to reduce the number of people infected with tick-borne diseases.

Updated March 8, 2024.

References

Galaxy Diagnostics. (2019). TBDWG recommendations for improved prevention of tick-borne disease transmission [Blog post]. Retrieved from: https://www.galaxydx.com/tbdwg-recommendations-for-improved-prevention-of-tick-borne-disease-transmission/

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018). Natural tick repellents and pesticides. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/prev/natural-repellents.html

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. (2010). Registration of a major change in labeling for 2-Undecanone as contained in Bite Blocker BioUD insect repellent and clothing treatment (EPA Reg. No. 82669-2) (Active Ingredient Code 044102) [Official letter signed by Maureen Serafini, Director, Bureau of Pesticides Management]. Retrieved from: http://pmep.cce.cornell.edu/profiles/insect-mite/propetamphos-zetacyperm/undecanone/biteblk_mcl_0810.pdf

Parks & Trails New York. (2018). Tick control in our parks. Retrieved from: https://www.ptny.org/newsandmedia/e-news-1/2018/06/tick-control-state-parks

Coin, G. (2019). Upstate NY Lyme disease expert: Prevention really works. Do it. NYup.com. Retrieved from: https://www.newyorkupstate.com/news/2019/05/upstate-ny-lyme-disease-expert-prevention-really-works-do-it.html

Toynton, K. et al. (2009). Permethrin general fact sheet. Corvallis, OR: National Pesticide Information Center. Retrieved from: http://npic.orst.edu/factsheets/PermGen.html

Brink, S. (2018). A guide to mosquito repellents, from DEET to … gin and tonic? NPR.org. Retrieved from: https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2018/06/30/623865454/a-guide-to-mosquito-repellents-from-deet-to-gin-and-tonic?utm_campaign=npr&utm_medium=social&utm_term=nprnews&utm_source=facebook.com

Olivier, J. (2017). The risk of Lyme disease on the Appalachian Trail is going to be high this year. OutsideOnline.com. Retrieved from: https://www.outsideonline.com/2168406/whats-risk-lyme-disease-appalachian-trail

Yim, W. T. et al. (2016). Repellent effects of Melaleuca alternifolia (tea tree) oil against cattle tick larvae (Rhipicephalus australis) when formulated as emulsions and in β-cyclodextrin inclusion complexes. Veterinary Parasitology, 225, 99-103. doi:10.1016/j.vetpar.2016.06007. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27369582