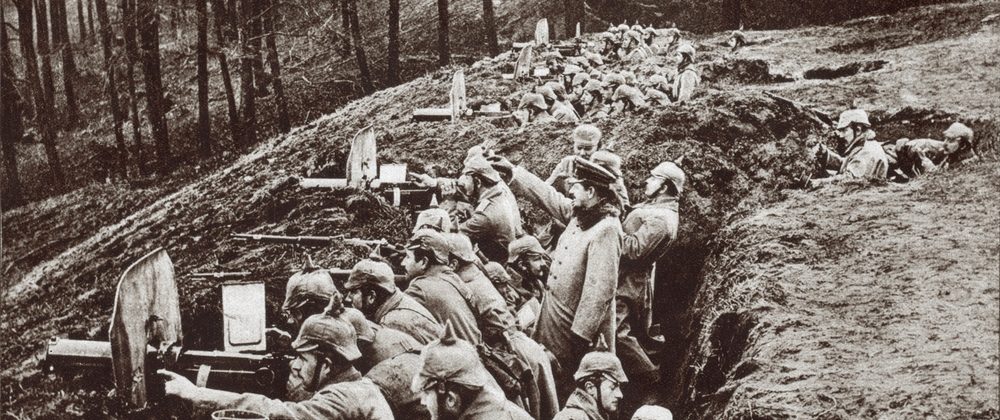

A recent string of trench fever cases in Denver, Colorado, has brought renewed attention to this infection caused by Bartonella quintana. The name “trench fever” comes from the conditions that soldiers in World War I faced. It was also called “five-day fever” during the war, reflecting the relapsing fever symptom that infected soldiers experienced. We previously wrote about the history of B. quintana infections and other Bartonella species.

So far in summer 2020, three cases have been confirmed and a fourth is suspected among unhoused individuals living in Denver who have no known associations with each other. In the United States, as many as one-in-three unhoused and underhoused individuals have been found to be infected by B. quintana. Research suggests that incidence is higher in individuals with alcoholism, though that may be a reflection of associated housing situations. The bacterium is spread by human body lice (Pediculus humanus), a risk unhoused individuals often face that is likely to increase during the social upheaval brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Societal disruption has previously been tied to increases in body lice infestations and subsequent outbreaks of B. quintana. Economic depressions and recessions, such as the recession of 2008, bring the disease to the forefront, likely due to increases in body lice infestations.

In addition to this clear association between body lice and B. quintana, other vectors and carriers should not be ignored when evaluating the risk of infection. B. quintana DNA has repeatedly been detected in C. felis (cat fleas, the most common species of fleas found on dogs and cats) and has been proven to survive in the gut and feces of the flea like B. henselae (the Bartonella species that causes cat scratch disease). B. quintana has also been found in samples collected from cats, dogs, monkeys and a variety of rodents.

Reports have linked direct transmission to a human from the bite of an infected cat and described co-infections with B. quintana and other Bartonella species. The evidence for B. quintana through routes in addition to body lice transmission seems clear.

Conclusion

Based on past global events, it is very likely that more cases of B. quintana will be diagnosed as pandemic disruptions continue. Tracing the source of the infections and protecting vulnerable individuals may require managing vectors and carriers beyond just body lice.

References

Evans, T. B. (2020, June 16). COVID-19 inequalities are striking and uncompromising. The Hill. Available at: https://thehill.com/opinion/healthcare/502903-covid-19-inequalities-are-striking-and-uncompromising

Hawryluk, M. (2020). An ickier outbreak: Trench fever spread by lice is found in Denver. Kaiser Health News. Available at: https://khn.org/news/an-ickier-outbreak-trench-fever-spread-by-lice-is-found-in-denver/

Kernif, T. et al. (2014). Acquisition and excretion of Bartonella quintana by the cat flea, Ctenocephalides felis felis. Molecular Ecology, 23(5) 12-4-1212. doi:10.1111/mec.12663 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24400877/

Al-Majali, A. M. (2004). Seroprevalence of and risk factors for Bartonella henselae and Bartonella quintana infections among pet cats in Jordan. Preventive Veterinary Medicine, 64(1), 63-71. doi:10.1016/j.prevetmed.2004.03.008 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15219970/

Bai, Y. et al. (2010). Enrichment culture and molecular identification of diverse Bartonella species in stray dogs. Veterinary Microbiology, 146(3-4), 314-319. doi:10.1016/j.vetmic.2010.04.017 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20570065/

Theonest, N. O. et al. (2019). Molecular detection and genetic characterization of Bartonella species from rodents and their associated ectoparasites from northern Tanzania. PLoS One, 14(10), e0223667. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0223667 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31613914/

Sato, S. (2015). Japanese macaques (Macaca fuscata) as natural reservoir of Bartonella Quintana. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 21(12), 2168-2170. doi:10.3201/eid2112.150632 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26584238/

Breitschwerdt, E. B. et al. (2006). Isolation of Bartonella quintana from a woman and a cat following putative bite transmission. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 45(1), 270-272. doi:10.1128/JCM.01451-06 https://jcm.asm.org/content/45/1/270

Breitschwerdt, E. B., & Maggi, R. G. (2019). Bartonella quintana and Bartonella vinsonii subsp. vinsonii bloodstream co-infection in a girl from North Carolina, USA. Medical Microbiology and Immunology, 208, 101-107. doi:10.1007/s00430-018-0563-0 https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00430-018-0563-0